Graduation Project

2020 - 2021

First Class Sculpture BA (Hons), Edinburgh College of Art.

Awarded the Clason-Harvie Bursary.

Selected for RSA New Contemporaries 2023.

First Class Sculpture BA (Hons), Edinburgh College of Art.

Awarded the Clason-Harvie Bursary.

Selected for RSA New Contemporaries 2023.

29/09/21

“establishing an understanding of not only the application but the sourcing of material.”

“I hope to create sculpture that is quiet and thorough.”

“establishing an understanding of not only the application but the sourcing of material.”

“I hope to create sculpture that is quiet and thorough.”

The Kunda Pair - Lipped Vessel, 2020, Ceramic.

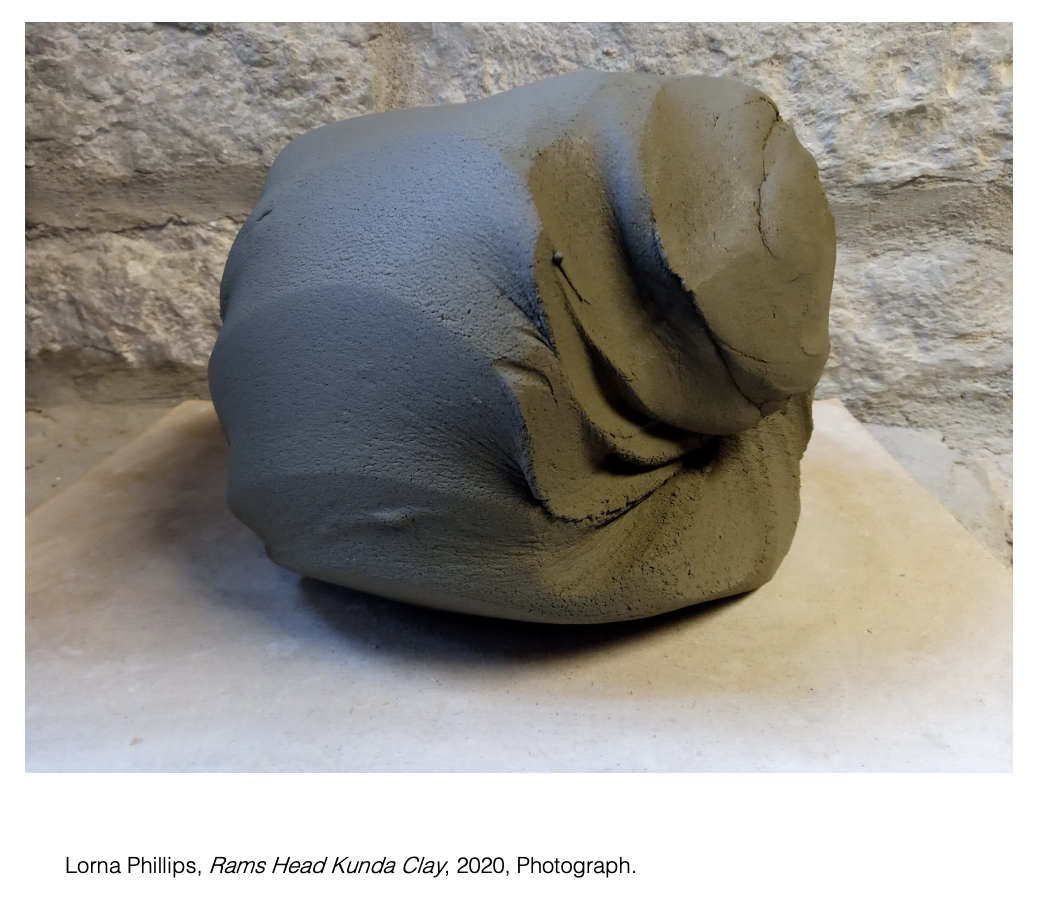

The sourcing of material from an area of

landscape formed my practice. Geological and archaeological papers have informed my actions. Working with clay through all it’s stages holds an

essential weight in my sculptural approach.

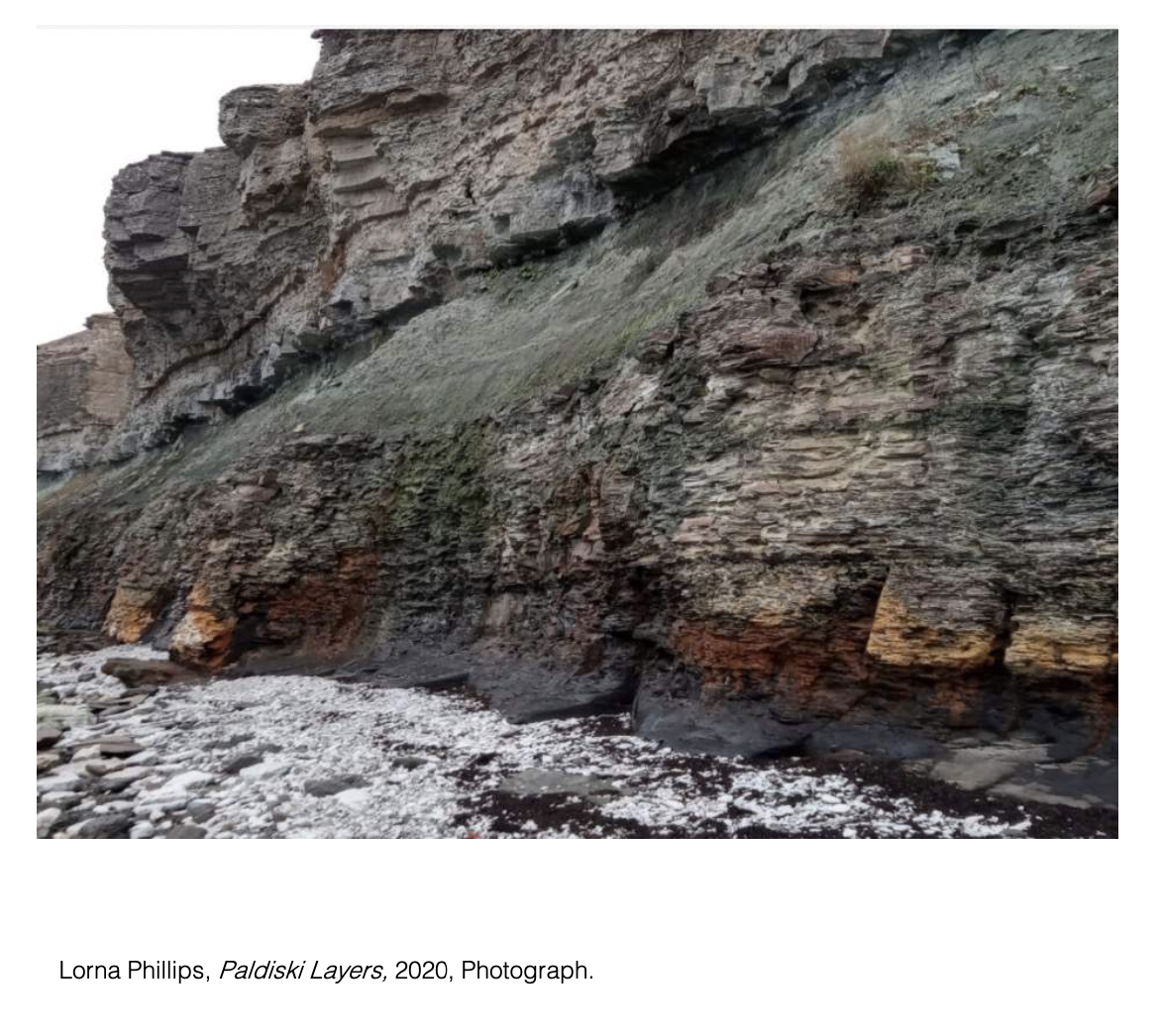

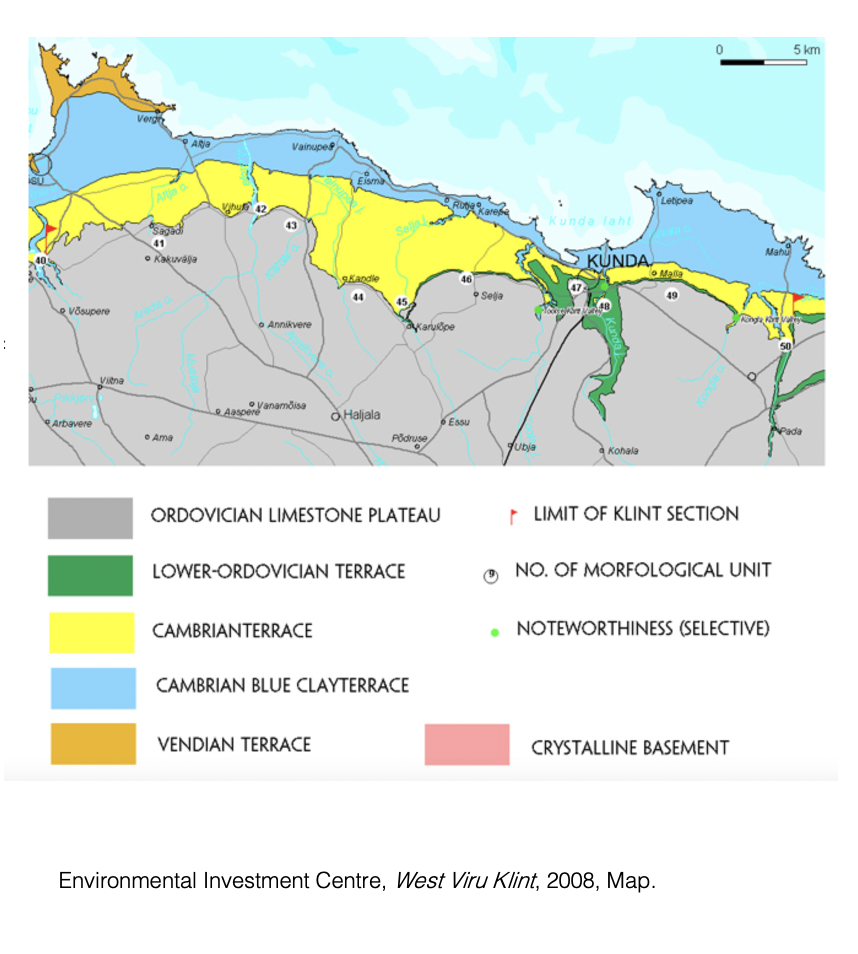

The landscape of Estonia was new to me. To be able to navigate this place and find the material key to my practice I had to learn of it’s geology. I discovered the Cambrian seam. This seam runs along the North Coast and is around 500 million years old. It was formed during one of the most influential evolutionary periods to the development of the human species (Marshall C. R. 2006).

Finding and digging the first piece of Cambrian clay at Kunda was the beginning of the tie between my practice and the land of Kunda.

The landscape of Estonia was new to me. To be able to navigate this place and find the material key to my practice I had to learn of it’s geology. I discovered the Cambrian seam. This seam runs along the North Coast and is around 500 million years old. It was formed during one of the most influential evolutionary periods to the development of the human species (Marshall C. R. 2006).

Finding and digging the first piece of Cambrian clay at Kunda was the beginning of the tie between my practice and the land of Kunda.

18/11/2020

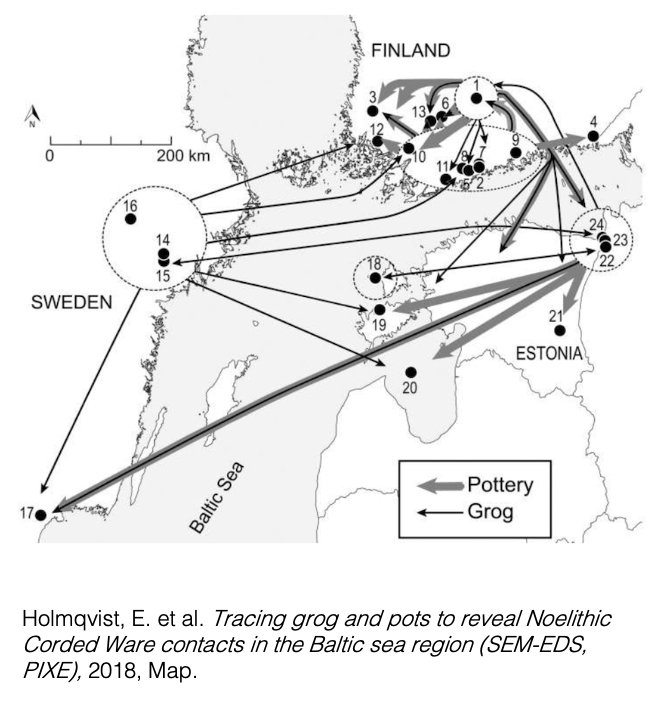

“Through analysis it has been found that when these women moved to a new place they took with them crushed sherds of pottery from their homeland, from the generations before them. ... Allowing for their work to carry time upon time. Working containing the work of those before is again carried into new work and so on and so on”

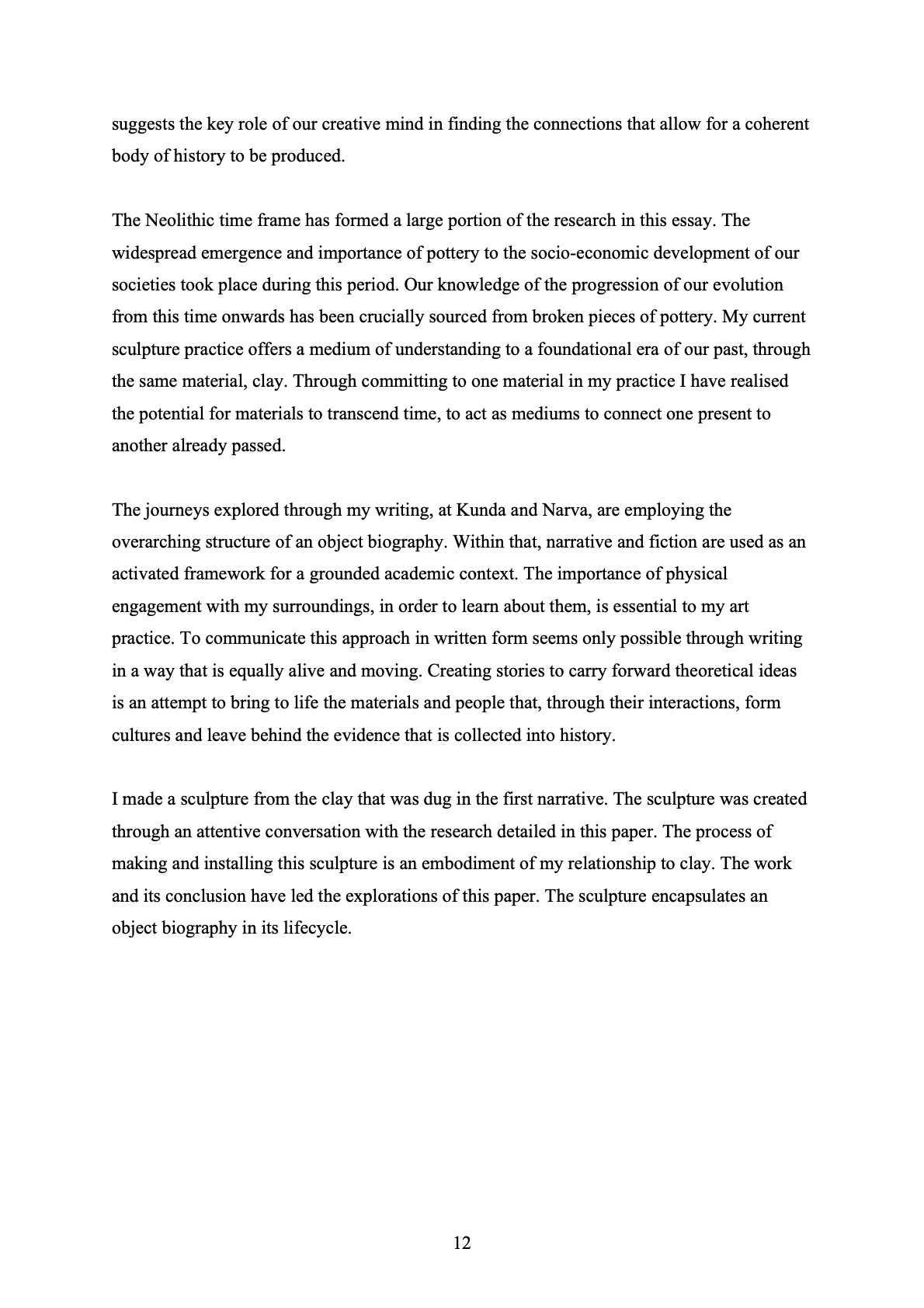

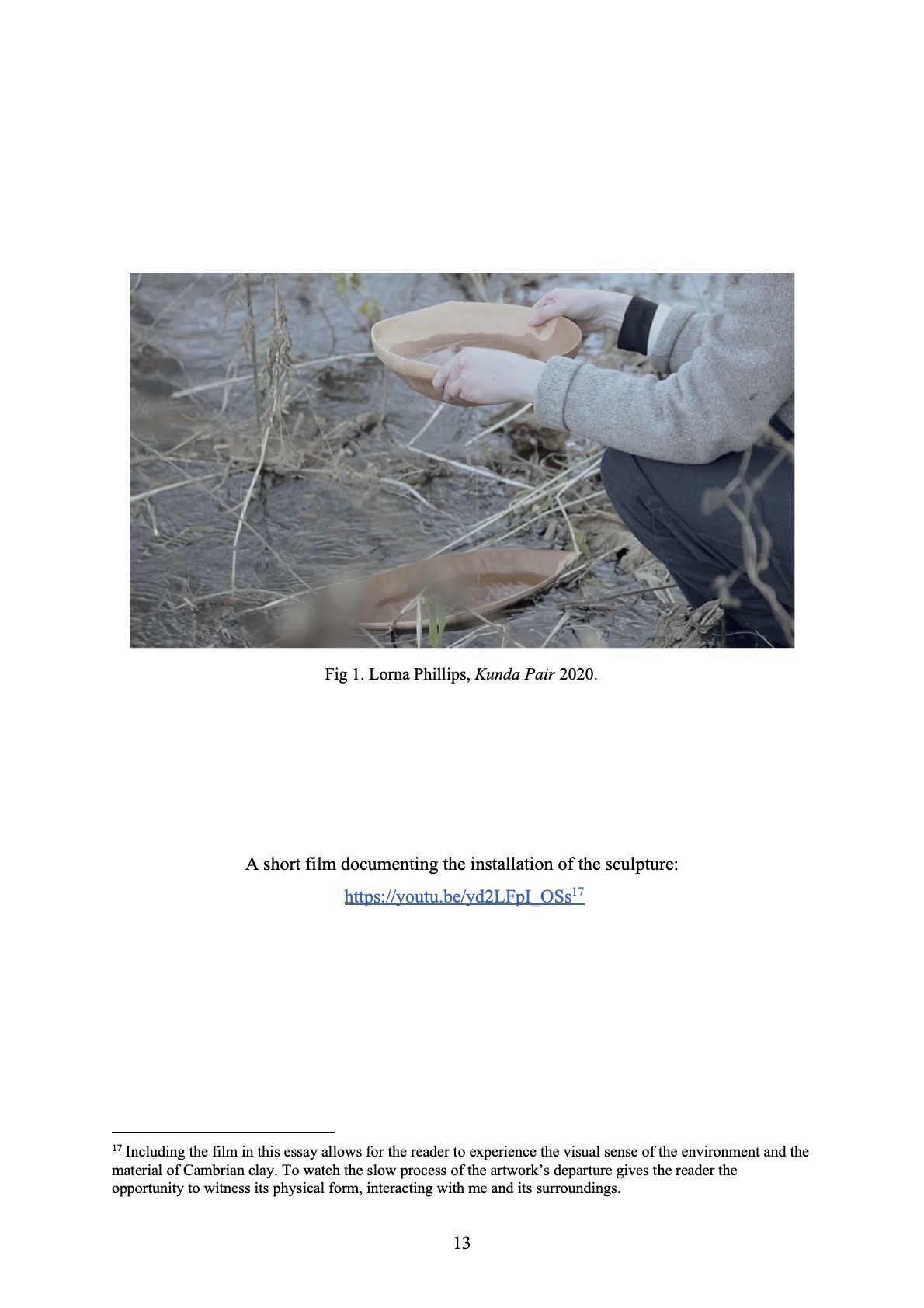

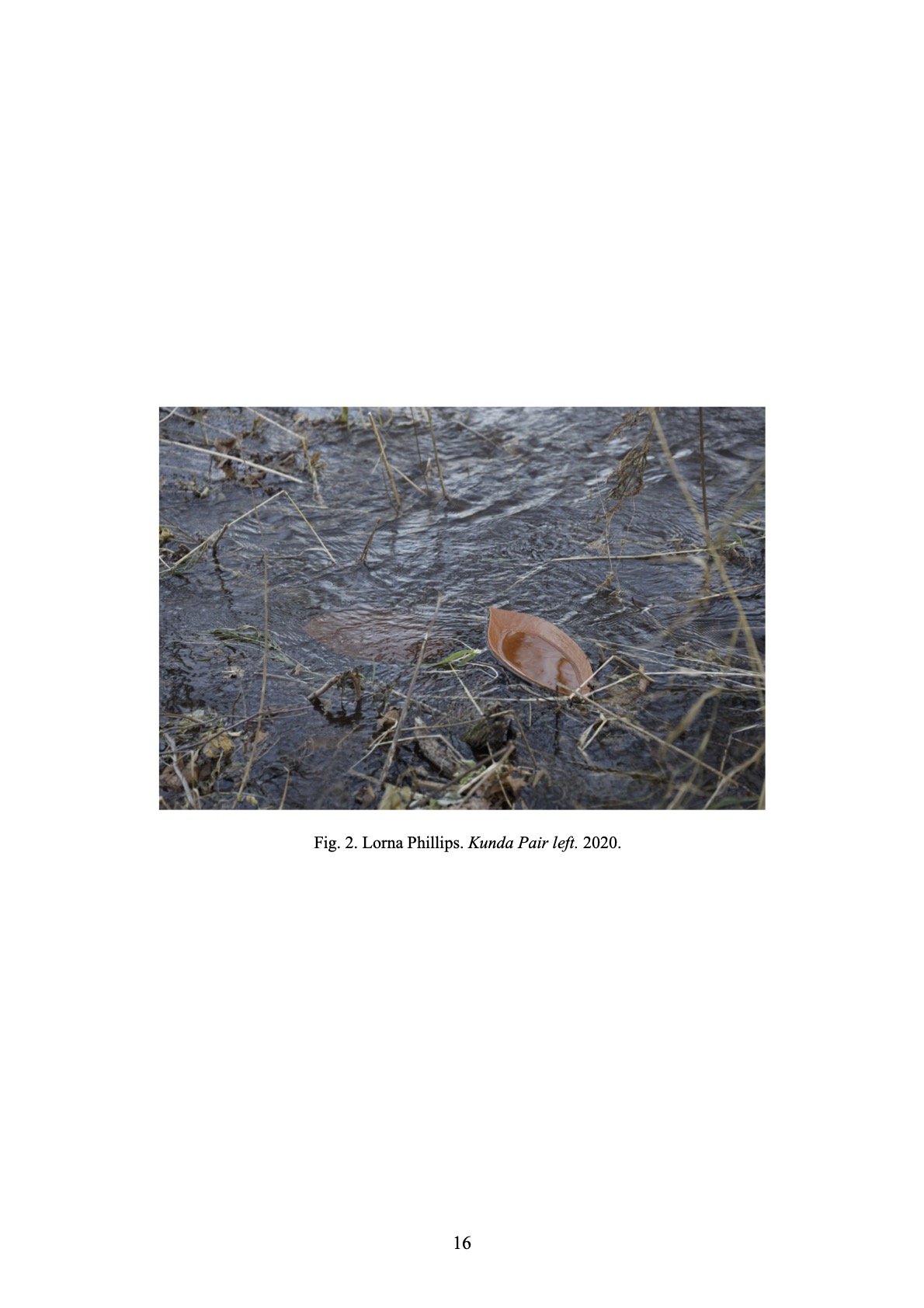

The Kunda Pair, 2020, Digital Film of Installation, 5 minutes 38 seconds,

(full version available at: https://youtu.be/yd2LFpI_OSs ), Filming by Ali Madani.

The empty ancient lakebed that is the present-day land of Kunda is the current source of the artist’s practice. The traces of the lake and its inhabitants are entered into conversation with, through the materials and forms that persevere. The river is the remaining artery that continues to flow through the land. Prehistoric artefacts have been preserved in the peatlands and mounds that have formed through the evolution of the landscape. The clay of Kunda continues to be mined, and worked, with hands. The relationship between the waterways of Estonia and the mining industry have heavily impacted the political and social identity of the land’s inhabitants.

As the ground groans underneath us it gathers the history of our actions within its layers.

The waterways of Estonia have played an influential role in the country’s social history and culture.

The past and current presence of water and extensive mining in the area of Kunda has resulted in it holding several important historical contributions to the evolution of Estonia’s people. Notably, the Phosphorite War, spurred by the threat of mining polluting a key watershed and changing the demographic, contributed extensively to the re-independence movement of Estonia, resulting in it’s freedom from Soviet rule in 1990.

The presence of the ancient lake of Kunda fuelled my fascination with the lifecycle of this landscape. To be able to see and hear of the changes in communities and their environment, and their continued relationship to their waterways.

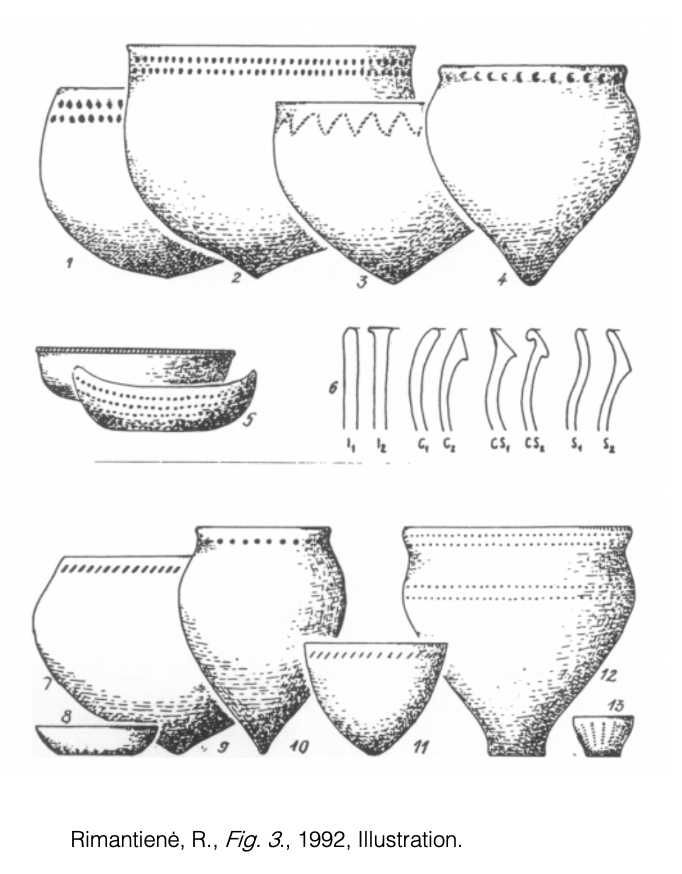

The work left by the makers of the earliest settlers breaking down into fragments that reveal the methods of their making, and their sensitivity and respect to their elders, gave an affirmation of the importance of clay and ceramic forms through time, to the formation of our societies and our understanding of our heritage.

The interactions of these communities with the waterways, and their travelling over, living around, and from the lakes and seas provided a continued connection between our time and the origin of our settlement on this land.

29/04/21

“After installing I walked away. ... I thought about the empty space that the lidded box held within it, that was now existing under and within the earth of the old island, for however long before it dissolves and collapses in on itself.”

“walking down the slopes of the hill, being able to feel the gradient through my bodies reaction to it, how steep or shallow it was. I have rarely felt such a fascination and curiosity for a specific hill.”

“After installing I walked away. ... I thought about the empty space that the lidded box held within it, that was now existing under and within the earth of the old island, for however long before it dissolves and collapses in on itself.”

“walking down the slopes of the hill, being able to feel the gradient through my bodies reaction to it, how steep or shallow it was. I have rarely felt such a fascination and curiosity for a specific hill.”

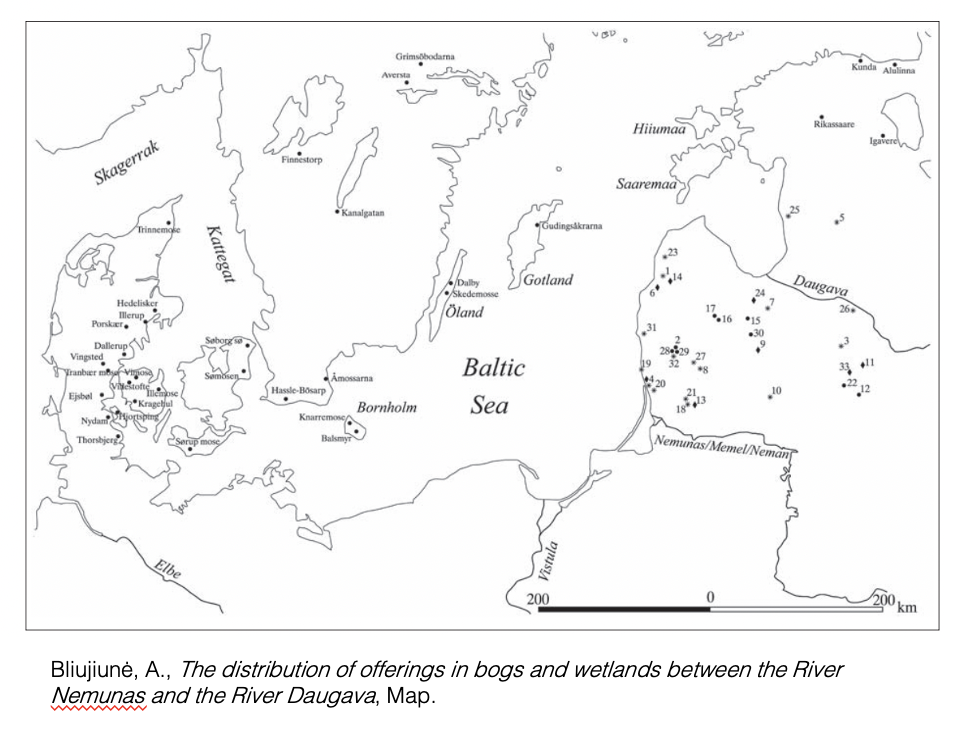

Votive offerings have been made to the

wetlands of Kunda in the past, treating water bodies and earth as

transcendental spaces, paths into the afterlife, a medium of connection between

our world and the greater powers.

A key intention in my practice was to find a way for the vessels I make to be held. Initially I presumed this would have to be a built structure.

I realised that the structures that have always held the pots are people. Until they are left, and then they are held by the landscape.

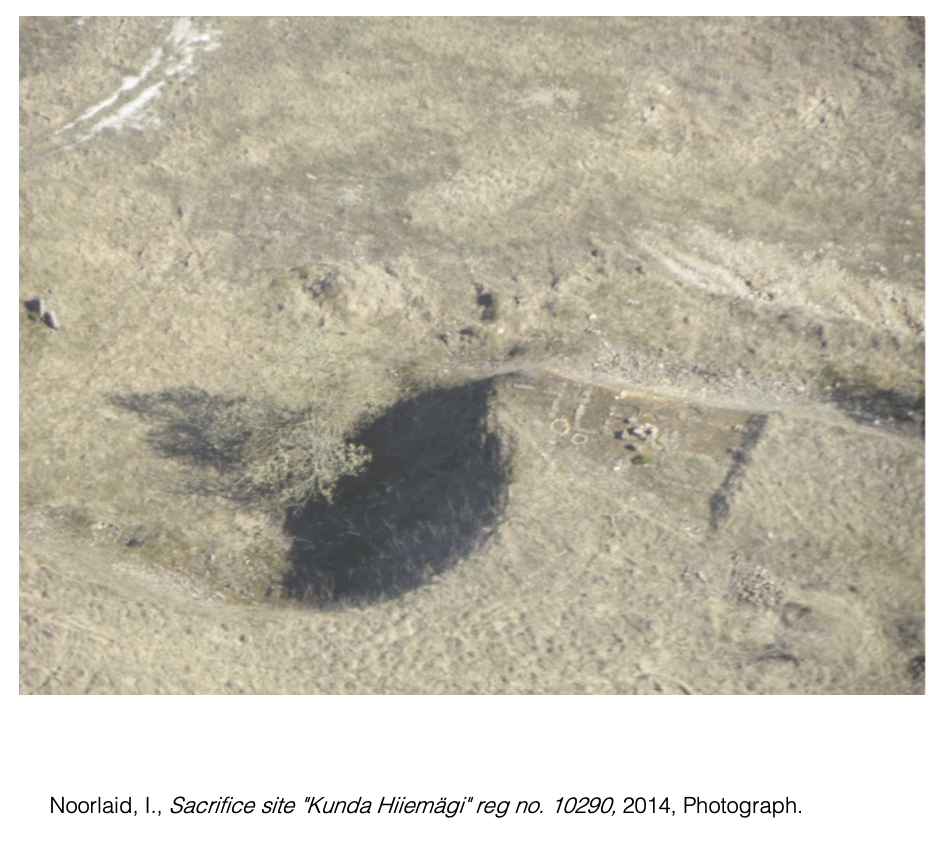

Another site of an installation, Hiiemägi, travelled to on foot, once held the lake of Kunda in. The remains of its burial grounds are crumbling into the quarried basin. It’s name translates to sacred hill, the history of it’s importance is carried forward within the language.

A key intention in my practice was to find a way for the vessels I make to be held. Initially I presumed this would have to be a built structure.

I realised that the structures that have always held the pots are people. Until they are left, and then they are held by the landscape.

Another site of an installation, Hiiemägi, travelled to on foot, once held the lake of Kunda in. The remains of its burial grounds are crumbling into the quarried basin. It’s name translates to sacred hill, the history of it’s importance is carried forward within the language.

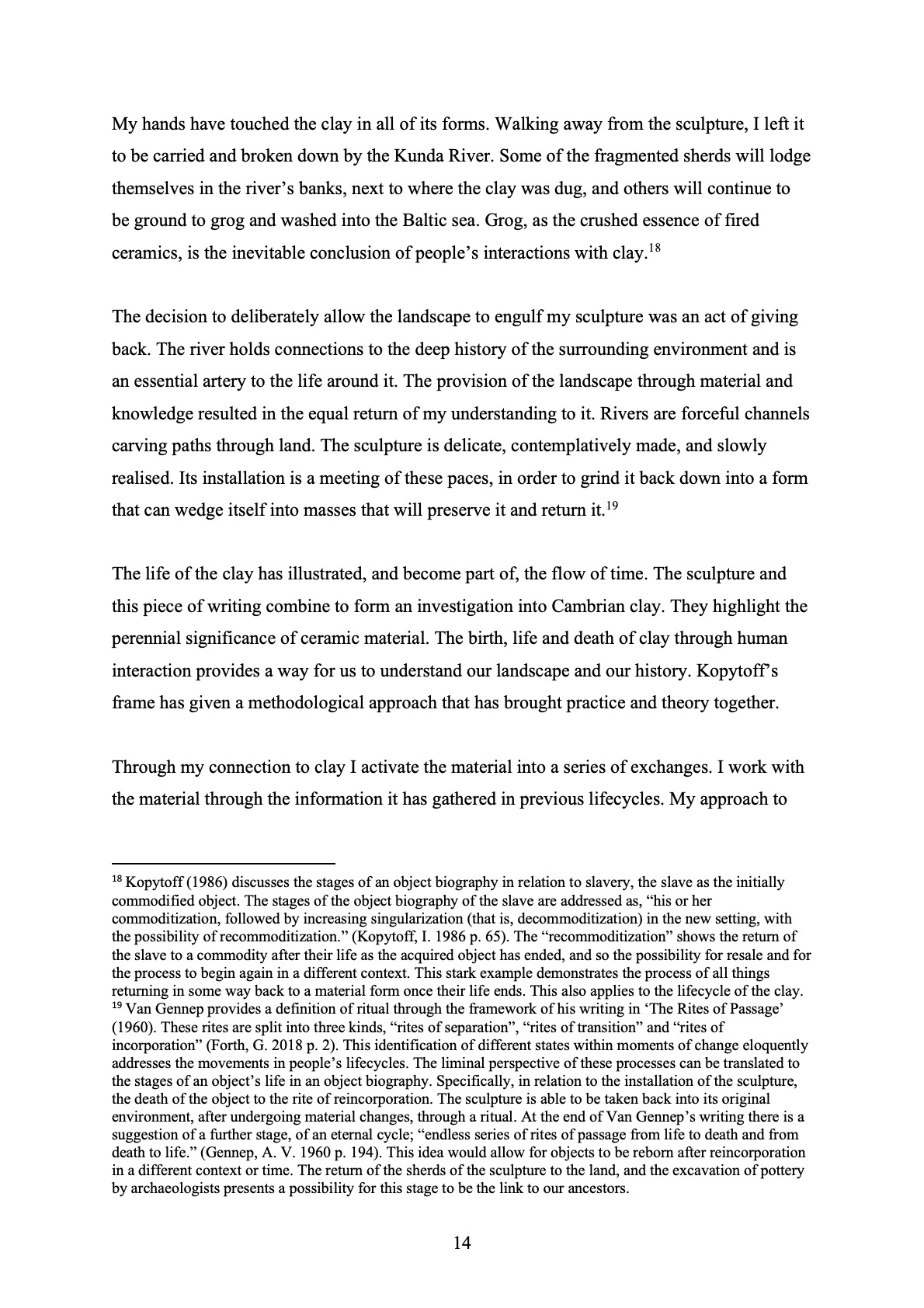

A Pot for a Mound on Hiiemägi, 2021, Digital Film of Installation, 2 minutes 42 seconds.

In their

migration their traces are scattered. The artist, as a young female maker and

aspiring craftsperson, engages with the history of female potters from the

earliest human settlers on the land. The stories of these women and their

journeys over the Baltic Sea reveal a respect for clay, their forebearers and

the natural environment that is incredibly beautiful. Driving the artist to

give something back to this understanding and intimacy with the earth and what

it holds. Encountering the land as a container of knowledge, history, lives

passed and continuing through their decay, as a foundation in all sense of the

word. Supporting, holding, and creating.

Giving offerings to sacred places, collapsing burial grounds, and past islands that are now sloping hills in flatlands. These are the actions compelled by a closeness formed to the physicality of the land that the artist finds themself in. Searching, touching, digging for an understanding, and through it finding a sensitivity and a deep sense of care for their surroundings, it’s heritage and culture.

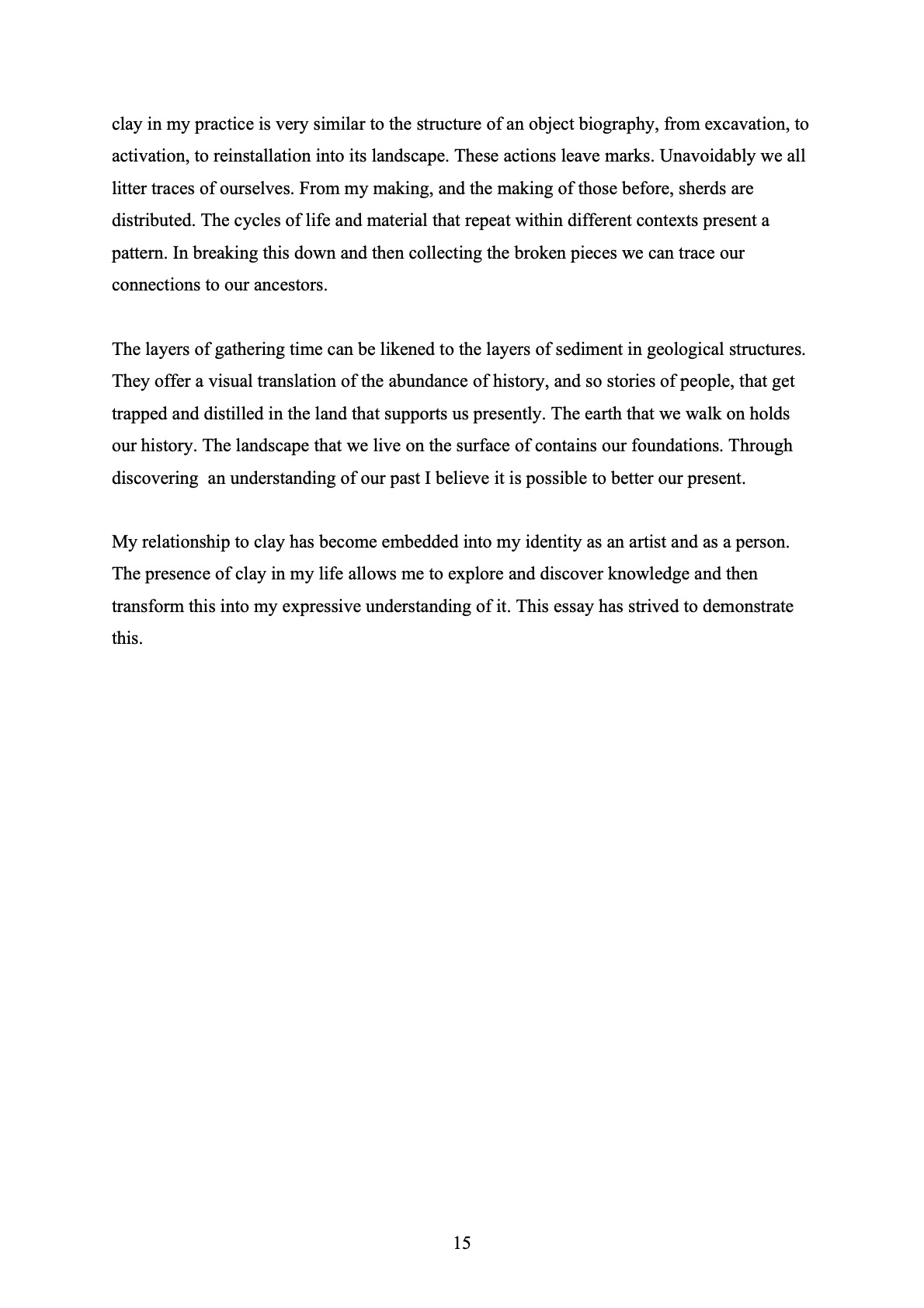

The Lammasmägi Burial, 2021, Digital Film of Installation, 2 minutes 11 seconds.

Giving offerings to sacred places, collapsing burial grounds, and past islands that are now sloping hills in flatlands. These are the actions compelled by a closeness formed to the physicality of the land that the artist finds themself in. Searching, touching, digging for an understanding, and through it finding a sensitivity and a deep sense of care for their surroundings, it’s heritage and culture.

01/12/20

“It has taken me a while to find the meeting point of function and expression in pottery in a way that is not overstating in any way that might be naive or unnecessary. I have been looking for a modesty, an understatement ...”

22/01/21

“The work is now out into people’s homes all around Estonia. I feel very warmly about this. It could really be felt how much people are connected to the land of this place.”

There are gestures

of gratitude in the work. The large moon jar (‘Thank you’) is made of two open

halves that surrender themselves to be one whole. The work will go to the

artist’s parent’s home. A gift back to those that have given so much. A gift to

those that support. The clays of the artist’s new home migrating to family

further afield.

Lucie Rie’s moon jar was brought from

Korea by Bernard Leach, “a gift to a deeply-loved friend” (Olding, 2017). Travelling

through many lives and exchanges it is a form that embodies the anonymous

craftsman and subdued beauty, continuing to hold an emotional message after the

passings of both Rie and Leach.

The wild

clays are dug, carried, and re-distributed. They are given in their

installation. To the land, the ancestors, and to people’s homes along the

coast. Works return to their source. The working is journeying through the

landscape. Entering people’s everyday lives, submerging its sherds into the earth,

and engulfing itself into the cycles of life, material and human, past and

present.

12/10/20

“From my journey and my carrying I feel an emotional attachment and engagement to the material. The memory and physicality of sourcing it provides me with a full understanding, not only of the clay itself but of the landscape that I am in and interacting with.”

“From my journey and my carrying I feel an emotional attachment and engagement to the material. The memory and physicality of sourcing it provides me with a full understanding, not only of the clay itself but of the landscape that I am in and interacting with.”

28/04/21

“There is absolutely no one up there. The moor runs and runs until there is a sharp drop, and after that large flat fields of farm land. It catches all of the wind coming in off of the sea up there."

The

short film Water

and Land expresses through spoken word, making, and the environment of installation

sites, the relationship between my actions, and my research. It captures the

experiences of walking through my environment as I learn and make around it. It

serves as both a finished work and a demonstration of my research practice.

The approach towards my practice has taken the form of a residency. I have learnt about my new environment through making and researching. The changes in circumstances of this year have not been easy. But it has resulted in a body of work that is in motion, actively moving through it’s installation.

The walking of the land is essential to my practice. The walking of the land is the movement of the work and of the practice.

The work exists through its erosion. This is the intention of my installations into Kunda.

The approach towards my practice has taken the form of a residency. I have learnt about my new environment through making and researching. The changes in circumstances of this year have not been easy. But it has resulted in a body of work that is in motion, actively moving through it’s installation.

The walking of the land is essential to my practice. The walking of the land is the movement of the work and of the practice.

The work exists through its erosion. This is the intention of my installations into Kunda.

Water and the Land, 2021, Digital Film, 12 minutes, 19 seconds.

The

artist’s personal stories are intertwined with the stories of people passed. Biographies

are found, created, and remembered through the clay. The land is shown to be

something at the very heart of human existence. It may be possible to hold the

clay but ultimately, we are held by it.

Lorna Phillips hopes to form understandings of unknown environments through the geology and archaeology of the land. With a wish to pursue the community of our surroundings as a source of wisdom. To move through times and cultures in order to learn from the past.

![]()

![]()

Lorna Phillips hopes to form understandings of unknown environments through the geology and archaeology of the land. With a wish to pursue the community of our surroundings as a source of wisdom. To move through times and cultures in order to learn from the past.

08/05/21

“When you look in from the top, the space inside is like looking into a giant pit, like falling off a cliff into a deep lagoon. ... The drop over edge of the rim into the big empty belly.”

28/04/21

“The grass on Hiiemägi was flattened into waves by the wind. The only things upright were trees and twigs. The curves of the grass perfectly summed up the way that the wind moves over the form of this piece of land. ... with the passing of these trees the land has been sculpted in another way.”

The artist’s blog from the beginning of their residence in Estonia, through the winter and into the spring, provided a way to capture the movements and moments in the overarching journeys. The writing of the blog became essential to the research and process of practice.

The work Kunda Pair is paired with a piece of writing, A Life of Clay, that explores the material of Estonian Cambrian clay through the lens of an object biography. The narratives and research involved in this writing are heavily intertwined with the making and installation of the artist’s work.

References:

Bliujienė, A. ‘The Bog Offerings of the

Balts: I Give in Order to Get Back’, Archaeologia Baltica 14. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/10603694/The_Bog_Offerings_of_the_Balts_I_Give_in_Order_to_Get_Back_(Accessed 10 April 2021).

Cardew, M. (1969) Pioneer Pottery. Harlow:

Longmans.

Cooper, E. (2012) Lucie Rie: modernist

potter. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

De Waal, E. (2015) The White Road. Vintage,

London.

Edmonds, M. (1999) Ancestral Geographies of

the Neolithic: Landscapes, Monuments and Memory. London: Routledge.

Environmental Investment Centre, 2008, West

Viru Klint, Available at: https://www.looduskalender.ee/klint/eng/16.html(Accessed 1 May 2021).

Gennep, V. A. (1960) The rites of passage.

Translated from French by M. B. Vizedom and G. B. Caffee. London: Routledge and

K. Paul.

Gosden, C., Marshall, Y. (1999) ‘The

Cultural Biography of Objects’. World Archaeology, 31 (2). pp. 169-178.

Available at: <https://www.jstor.org/stable/125055> (Accessed 25 October

2020).

Holmqvist, E., Larsson, A.M., Kriiska, A.,

Palonen, V., Pesonen, P., Mizohata, K., Kouki, P. & Räisänen, J. (2018)

‘Tracing grog and pots to reveal Neolithic corded ware culture contacts in the

Baltic Sea region’. Journal of Archaeological Science, 91. pp. 77-91. Doi:

<https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2017.12.009>.

Ingold, T. (2021) Correspondences. Polity

Press, Cambridge.

Jonuks, T. 2007, ‘Holy Groves in Estonian

Religion’, Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 11 (1), pp. 3-35. Available at:

<https://kirj.ee/public/Archaeology/2007/issue_1/arch-2007-1-1.pdf> (Accessed 3 February 2021).

Kopytoff, I. (1986) ‘The cultural biography

of things: commoditization as process’. In: Appadurai, A. (Ed.) The Social Life

of Things: Commodities in cultural perspective. pp. 64-92. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press

Kriiska, A. (1996) ‘The Neolithic Pottery

Manufacturing Technique Of The Lower Course Of The Narva River’. Coastal

Estonia, Recent Advances in Environmental and Cultural History, PACT 51,

Rixensart. pp. 373-384. Available at:

<http://webdoc.sub.gwdg.de/ebook/o/2004/ethesis.helsinki.fi/julkaisut/hum/kultt/vk/kriiska/te

kstid/06.html> (Accessed 24 November 2020).

Kriiska, A. (2000) ‘Corded Ware Culture

Sites In North Eastern Estonia’. Muinasaja teadus. 8. pp. 59-79. Tartu: University

of Tartu. Available at:

<http://webdoc.sub.gwdg.de/ebook/o/2004/ethesis.helsinki.fi/julkaisut/hum/kultt/vk/kriiska/tek

stid/05.html> (Accessed 10 November 2020).

Kriiska, A. & Sander, K. (2018) ‘New

Archaeological Data And Paleolandscape Reconstructions Of The Basin Of An Early

And Middle Holocene Lake Near Kunda, North- Eastern Estonia’. Fennoscandia

Archaeolgica, XXXV. pp. 65-85. Available at:

<http://www.sarks.fi/fa/PDF/FA35_65.pdf> (Accessed 25 November 2020).

Leach, B. (1940) A Potter’s Book. Faber and

Faber Ltd, London.

Marshall, C. R. (2006) ‘Explaining the

Cambrian “Explosion” of Animals’. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary

Sciences, 34. pp. 355-384. Available at: <

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.earth.33.031504.103001> (Accessed 5 January

2021).

McFarlane, R. (2016) Landmarks. Penguin,

UK.

Noorlaid, I. and Abel M., 2014, 2009.

Register of cultural monuments. Available at: https://register.muinas.ee/public.php?menuID=monument&action=imagegallery&id=10290(Accessed 1 May 2021).

Olding, S. (2017),

‘The Moon Jar: A Trascendentant Ceramic Form’, Modern Masters. Available at:

<https://www.phillips.com/article/10680842/the-moon-jar-a-transcendent-ceramic> (Accessed 5 May 2021).

Piezonka, H., Meadows, J., Hartz, S.,

Kostyleva, E. L., Nedomokina, N. G., Ivanishcheva, M., Kosorukova, N. and

Terberger, T. (2016) ‘Stone age pottery chronology in the Northeast European

forest zone: New AMS and EA-IRMS results on foodcrusts’. Radiocarbon, 1 (2),

pp. 1-23. Available at: 10.1017/RDC.2016.13 (Accessed 4 May

2021).

Rimantienė, R., (1992)

‘The Neolithic of the Eastern Baltic’. Journal of World Prehistory, 6 (1), pp.

97-143, Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25800611 (Accessed 7 May 2021).

Smith-Estrada, C. (2011) Estonians stop

toxic phosphorite mining, 1987-88. Research report, Global Nonviolent Action

Database. Available at: <

https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/estonians-stop-toxic-phosphorite-mining-1987-88

> (Accessed 2 November 2020).

Spector, J. (2009) What This Awl Means;

Feminist Archaeology at a Wahpeton Dakota Village. St Paul: Minnesota

Historical Society Press.

Tuuling, I. and Flodén, T. (2016) ‘The

Baltic Klint beneath the central Baltic Sea and its comparison with the North

Estonian Klint’. Geomorphology, 263, pp. 1-18. Available at: <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169555X1630126X>

(Accessed 10 December 2020).

University of Helsinki. (2018) ‘Skilled

female potters traveled around the Baltic nearly 5,000 years ago’. ScienceDaily.

Available at: <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/03/180322112659.htm>

(Accessed October 24).

University Of Tartu Faculty Of Philosophy

Institute Of History And Archaeology. Kristjan Sander. Kunda Lammasmäe Stone

Age Settlement. Master’s thesis Supervisor: Professor Aivar Kriiska. Tartu

2014.

Yanagi, S. (2017) The Beauty of Everyday

Things. UK: Penguin Classics.

Student Feature on the University of Edinburgh Graduate Show Website 2021:

https://www.2021.graduateshow.eca.ed.ac.uk/news/student-moves-north-estonian-coast-final-year-studies

Interview by Eva Coutts: https://www.2021.graduateshow.eca.ed.ac.uk/news/lorna-phillips-sculpture

‘The Show Must Go On: Scottishe Degree Shows 2021’. The Skinny, Scotland’s Independent Arts Magazine:

“After a year of all different kinds of displacement, Lorna Phillips’ practice takes place outside, by an empty ancient lakebed in Kunda, Estonia. Phillips has worked with clay taken from the site, making well-crafted pots and vessels using techniques practised since the earliest human settlements on the land.”

By Adam Benmakhlouf and Katie Dibb, 25th June 2021

https://www.2021.graduateshow.eca.ed.ac.uk/news/student-moves-north-estonian-coast-final-year-studies

Interview by Eva Coutts: https://www.2021.graduateshow.eca.ed.ac.uk/news/lorna-phillips-sculpture

‘The Show Must Go On: Scottishe Degree Shows 2021’. The Skinny, Scotland’s Independent Arts Magazine:

“After a year of all different kinds of displacement, Lorna Phillips’ practice takes place outside, by an empty ancient lakebed in Kunda, Estonia. Phillips has worked with clay taken from the site, making well-crafted pots and vessels using techniques practised since the earliest human settlements on the land.”

By Adam Benmakhlouf and Katie Dibb, 25th June 2021